Continuing a discussion on an old thread, perhaps we can ask: “Will there be police and prisons under socialism?”

I’m sure there will be a number of different answers from socialists, but this is c/abolition, so of course the answer would be no.

But wait, one might say, weren’t and aren’t there police and prisons in “actually existing socialism”? Yes, but for varying reasons, the “socialism” of these projects was merely the political ideology of their ruling parties, not in terms of their mode of production. All of these countries had wage-labor, proletarianization, money, commodities, et cetera—all features of a capitalism. Because they had these features of capitalism, these state socialist projects necessarily needed police and prisons to enforce the rule of state capital.

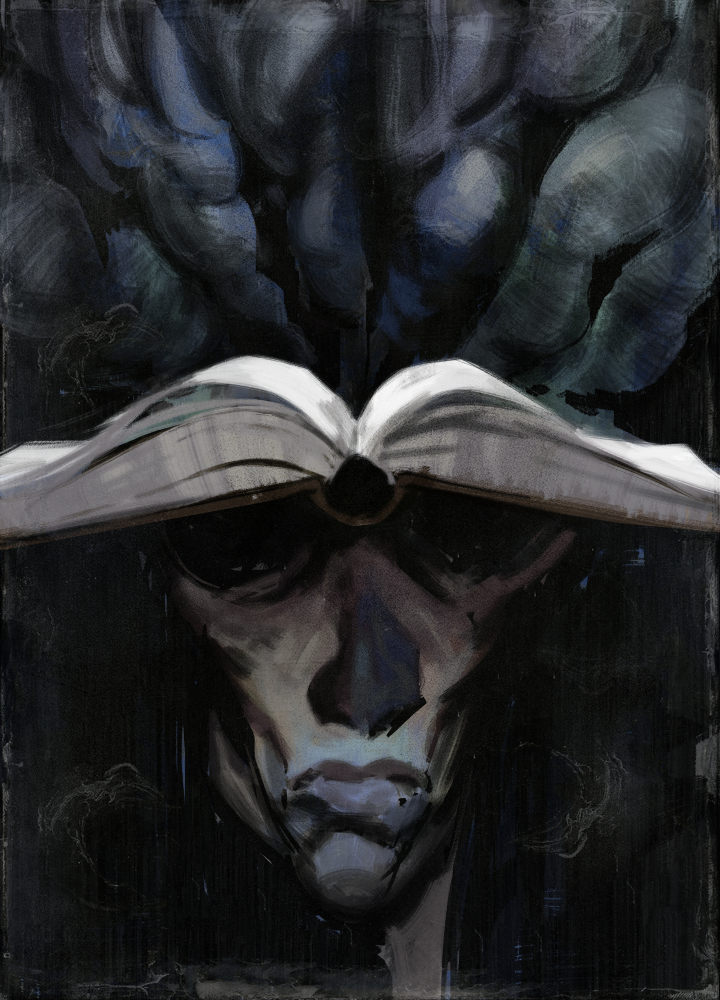

When Marx talked about socialism, he most clearly outlines it in his Critique of the Gotha Program where he uses the term “lower-phase communism” that Second International Marxism and later pre-Bolshevized Comintern Marxism interpreted as “socialism.” In socialism or lower-phase communism, the state is already abolished because classes are already abolished. In doing so, we can necessarily expect the cruelest features of the state like police and prisons are necessarily also abolished.

Police and prisons are historically contingent to class society. They serve as a mode of upholding class society. Across Europe and North America during the development of capitalism, police and prisons were used to enforce the rule of wage-labor and force previously non-proletarian peoples into proletarianization. These institutions would drive people off their land, enclose the commons, and then impose regimes of terror to enforce class society.

But how about, a socialist might ask, the enforcement of class rule of the proletariat? The dictatorship of the proletariat? First, it is important to note that the dictatorship of the proletariat is not yet socialism. It is the transition period to socialism. Second, the dictatorship of the proletariat is indeed a class dictatorship, just like the dictatorship of the bourgeoisie we currently live under. Third, the class dictatorship of the proletariat cannot look like previous modes of class dictatorship because it is a class dictatorship for the transition from a class society to a classless society, not a transition from a class society to another class society. Previous modes of class dictatorship used the terror of police and prisons to transition from a monarchist system to a republican system, or the class dictatorship of the aristocracy to the class dictatorship of the bourgeoisie. The proletarian class dictatorship is different in that it is a class dictatorship that abolishes class distinctions, the most important of which is proletarianization. Logically, if proletarianziation needs police and prisons to be enforced, then the class dictatorship to abolish proletarianization likewise does away with police and prisons, simply because one cannot use the enforcement of proletarianization to do away with proletarianization.

However, the crucial feature of class dictatorship is its dictatorship, the ability for a class to enforce its will on all other classes. We have previously noted here that previous modes of class dictatorship does this using police and prisons. How is proletarian class dictatorship supposed to do this without police and prisons? Very simply, the power of a proletariat as a class-for-itself does not come from the barrel of a gun or a ballot box, but by their ability to subvert what they are as proletarianized beings. This does not mean that there will be no violence, far from it, but that this violence is ordered towards subversion of class society rather than reproducing it. Commonly, Second International Marxism, especially as embodied by Lenin in State and Revolution, advocates for a whole armed proletariat as opposed to special bodies of armed force (e.g. police and prisons). For whatever reason, Lenin disregarded this when the Bolsheviks took power in Russia, thus reproducing class society and all that that entailed, leading the Soviet Union down a path of an unambiguous class society where the proletariat continued to be proletarianized.

Abolition communism means moving beyond this failure to abolish police and prisons under a transitional period and forwarding abolition and communization in its place.

So no, there would not be police and prisons in socialism nor in the transitional period to it, unless of course that transitional period was not transitioning to socialism at all but back to capitalism.

I challenge you then to think, why is it that these functions (your numbers 1 and 2) are solely the purview of a special body of armed men? Right now people at the margins deal with harm in a healthy, restorative, and transformative way, and they have been doing this because they are Black, Indigenous, Queer, feminized, criminalized, or whatever other context that prevents them from turning to the police. So because of this, they had to develop ways of dealing with harm without invoking a special body of armed men.

As for your functions 3 to 5, why do you need to detain these people? Will detaining them help them resolve the issues that make them violent or “disruptive”? Will it help them with their mental issues? To transform their energies from violence? It’s ridiculous to even suggest a prison would. Reformed ex-prisoners are reformed in spite of, not because of, prisons. No society before ours chain millions of people into cages like we do today. You can try out reading Instead of Prisons.

As for who finds missing people, who investigates the mysteries, maybe detectives can continue to exist, not as special bodies of armed men, but as servants of society like a social worker. Maybe they can be adventurers or something like some kind of scooby doo gang. Maybe maybe maybe, all this talk is pointless for us now. Seeds in this society can grow to alternative possibilities tomorrow. What matters is that the non-violent functions that policing has usurped from society can return to communities who can then decide on how these functions can and ought be carried out.

Being from the UK I didn’t automatically consider them to be armed, but sometimes that is unfortunately necessary if the situation is dangerous enough. Surely you will need armed men in your ideal society also - forces from the outside may attempt to subvert it, and if a crisis emerges, order may break down.

I didn’t say prisons necessarily help people, and I agree with you that if anyone is reformed by prison, it’s in spite of the system. I think of a prison as a way to protect the innocent from dangerous people, but in most cases I disagree with sending non-violent offenders there.

Thanks for the book recommendation. I’d be keen to imagine another way forward, so maybe that’ll help me with some ideas, or at least understand the abolitionist viewpoint. I can see from skim-reading the preface that it attempts to answer many of my questions.

Hmm, I forgot the UK doesn’t arm their rank-and-file police. As it happens, that’s one of the major transitional demands of the abolitionist movement. That’s not enough, however. Even from my vantage point fro the global south, I can see how the law is used unevenly in the UK, repressing the progressive forces but giving right wing forces a pass.